The Divine in everything

Nishant R

spiritualgym2@gmail.com

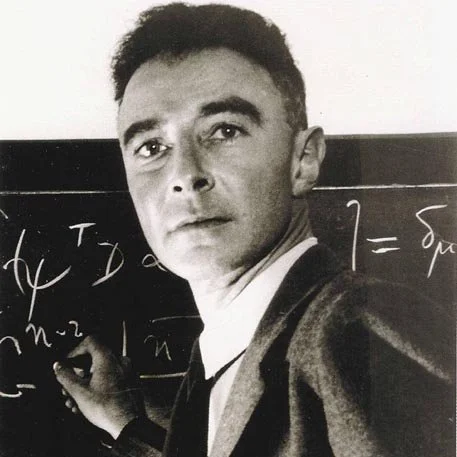

Image: J Robert Oppenheimer

Climate change and natural disasters, the likely return of Covid-19, and economic challenges, all can make it seem as though the world is in a downward spiral (mid you, some have probably been preaching that we were the Last Days since shortly after the first one).

Yet for me, I see not so much that everything is divine (as someone said, ‘Why would you invent a wasp?’), but that the Divine is in everything.

We know that, to a greater or lesser extent, how we as humanity have lived and worked in the world has contributed and is contributing to the global impact of climate change (how much we have been and remain responsible is, of course, a subject of sometimes violent debate, as is what we should do about it, how much and how fast).

If, as I do, you believe that there is some Supreme Plan for humanity, it must involve us recognising our limitations and our responsibilities, that the world is more than just ourselves, and that everything around us in Nature has a role to play, even if we don't understand that role fully (Wasps?).

That does not mean that there is some end-state that we will reach in our lifetimes or in ourselves.

In John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Apollyon, the angel of the bottomless pit, tells the pilgrim Christian ‘Strive here for mastery’. For too many, that striving seems to aim at mastering others rather than mastery of ourselves, seeking to control how others live their lives. Since Apollyon’s name in Greek means 'Destroyer' (in Hebrew ‘Abaddon’: 'Doom' or 'Destruction’),, you might think that following his advice might not lead to the best end-result.

Thus, J Robert Oppenheimer, who led the team to create the atom bomb, when he saw the result in July 1945, quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” (Sanskrit scholar Stephen Thompson suggests ‘“world-destroying time” as a better translation of the original Sanskrit than “Death”, and the use of the phrase reflects Oppenheimer’s own struggle to accept the idea of destruction as illusion. The words are spoken by Krishna for the benefit of the reluctant soldier Arjuna, intended to convey a message that irrespective of what Arjuna does, whether he joins the fight or not, everything is in the hands of the divine).

None of us are likely to be called upon to work to such cataclysmic ends, so what to do?

Recognising the divine in everything, in the world in which we live, in others as individuals and as groups, is a start. It enables us to avoid demonising groups, whether refugees or migrants seeking a better or safer life, or people of one particular faith, culture, race, identity or ethnicity. Perhaps it begins with accepting the value inherent in other people, those close to us and those with whom we barely come into contact.

Seeing the divine in everything is the reverse of the maxim ‘God’s in His heaven, all’s right with the world’, since, clearly, everything is not alright.

In Candide, the French author Voltaire stated, ‘We must cultivate our garden’, but again, that’s a starting point not an endpoint. The edge of the garden is not a fence to stop the rest of the world intruding: gardens have gates, and we are expected to pass through them.

We do what we can do. We can strive to do more and may even achieve it. But ambition needs to be accompanied by action.

It is the action – which can involve outward engagement with and support for others, or could involve spending more time in meditation or prayer to build self-awareness as a driver of self-growth – that validates.

What is important is not why we do it, but that we do it.